It’s never been more important for education systems to demonstrate impact from their professional learning programs. The policy shift from test-based outcomes to more flexible, comprehensive success standards has brought new possibilities — and challenges — to every level of operations, and evaluating professional learning is now a must.

Join KickUp as we examine six of the most common roadblocks to thriving data cultures. With practical tips, guiding questions, and real-life examples of districts excelling through data, you can push your professional learning program to new levels of effectiveness.

Like an engine, continuous improvement requires the right fuel — in this case, data — to function. Too often, school district leaders find they might have data, but not the kind that can actually drive improvement work.

Maybe you’re thinking you have data—spreadsheets and spreadsheets of it—but it’s being used to make isolated decisions with unclear coach and educator buy-in. Maybe your facilitators are working hard to build interventions that reflect educator interest but sometimes at the cost of alignment to your strategic initiatives.

Or maybe you know in your gut that your professional learning is supporting your teachers but you need evidence to protect your instructional coaching program from a tough season of budget cuts.

In this free KickUp series, you’ll find resources to help you move from theory to action. Specifically, you’ll:

The adoption of No Child Left Behind in 2001 ushered in an era of “data-driven accountability” that, while well-intentioned, has led to very minimal gains in student achievement. In recent years, “being data-informed” has expanded beyond student test-scores, permeating district culture so deeply that we’re collecting more data than ever. Our meetings center around data reviews. We’ve built and staffed full data and analysis teams. We’ve gone from top-down structures to asking our stakeholders for so much feedback that we have to create spreadsheets and calendars just to keep track of it all.

But not all data is useful data. Despite the multitude of data we’re collecting, we’re often no closer to clarity. In some ways, we’ve gone from a desert to a dense forest: drastically different landscapes but equally difficult to traverse. The answer isn’t to stop collecting professional learning data: it’s to clarify and streamline so that our data is actionable.

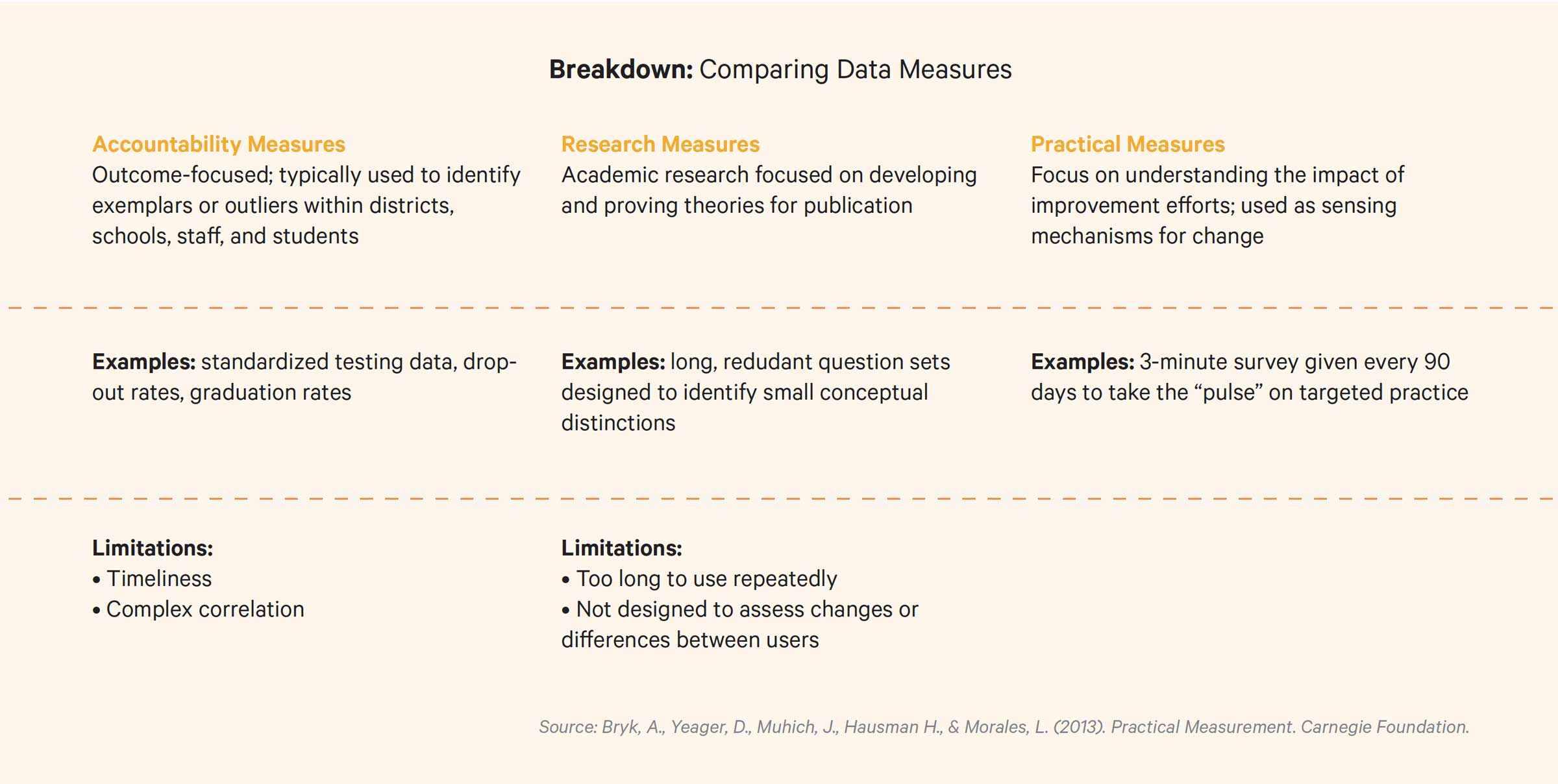

You’ve likely heard the phrase “Data rich, insight poor.” Unfortunately, much of the data we’re collecting is often meant for other work like accountability or research. When we try to use that data to drive continuous improvement in our professional learning, it falls short.

In the push to close the opportunity gap, one universal truth has emerged: teachers can have the greatest impact on student achievement (Darling-Hammond, 2000). In response, we’ve dedicated time and poured resources into improving teacher practice as a lever for improving student outcomes.

The increased urgency behind shifting instructional practice has ushered in an ever-increasing number of new curriculum methods that teachers and school districts are expected to implement. From Common Core to social-emotional learning to STREAM, we have an overwhelming number of new models and strategies for meeting a wide array of learning styles.

At the same time, school districts are making large “bets” on expensive, job-embedded learning methods that add complexity to the system. We’ve moved from single one-day workshops to professional learning that is continuous, job-embedded, and personalized to the adults it supports. This means the advent of coaching, population-specific strategies (like new teacher inductions or academies), and ongoing support models. Without a laser-like focus on aligning these supports around a common goal or outcome, there’s an even greater risk of not hitting any targets.

The double whammy of new teaching methodologies and new intervention strategies results in a system that’s more complex from all angles—and the pressure to improve and demonstrate impact is growing with it. The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) requires all interventions be evidence-based, while resources for professional learning like Title II-A are always at risk.

The demand for data is clear, and it goes beyond compliance. Gathering and using actionable data to continuously improve professional learning holds the key to solving three core problems: managing the complexity of professional learning, shifting teacher instructional practice, and demonstrating professional learning impact to ensure their sustainability.

Most of our data issues can be tied to two stages: the design and the implementation. Let’s revisit the common data issues we described above, starting with those that can be attributed to design.

PROBLEM 1

The data isn’t connected to the practice being changed

How to connect teacher PD, logic models, and learning goals

PROBLEM 2

The data focuses on vague or subjective outcomes

How to define professional learning goals for teachers

PROBLEM 3

The data is collected too soon, before change can reasonably occur

How to make a teacher PD data calendar

PROBLEM 4

The data is too resource-intensive to collect

How to create a centralized PD data system

PROBLEM 5

The data isn’t easily understood by the people using it

How to build data-savvy education PD teams

PROBLEM 6

The data isn’t shared and used frequently within the planning team

How to schedule consistent data checks for PD programs

Schedule a demo with one of our friendly team members.