It’s never been more important for education systems to demonstrate impact from their professional learning programs. The policy shift from test-based outcomes to more flexible, comprehensive success standards has brought new possibilities — and challenges — to every level of operations, and that includes professional learning.

Join KickUp as we examine six of the most common roadblocks to thriving data cultures. With practical tips, guiding questions, and real-life examples of districts excelling through data, you can push your professional learning program to new levels of effectiveness.

The secret to maintaining any routine is making it easy for yourself. Want to squeeze in more early-morning workouts? Pack your gym clothes the night before. Trying to keep the mail from piling up? Keep a wastebin next to the mail table. And if you’re trying to build a habit among a group of people — like consistently and thoroughly responding to feedback surveys, for example — the trick is to simplify and streamline wherever possible, for both the audience and yourself.

Today: running large-scale data projects while respecting your teachers’ time — and your own.

TACKLING COMMON DATA ISSUES | PROBLEM 4

Timelines, as we’ve said, are tricky. Educators may be the most reliable source of on-the-ground classroom insight, but they’re people too — people with some of the toughest jobs around. So how do you design data collection methods and schedules that respect their time while ensuring maximum high-quality responses?

Manually collecting every piece of data you’ve decided to track just isn’t feasible.

For example, let’s say you decide that “opportunities for student discussion” will be a key metric for evaluating new student-teacher interaction training. The most perfect way of collecting it might be to have every teacher record a time log of when students were discussing in their classroom. But a daily time log isn’t practical: the time required to roll it out and gather the data is prohibitive to effective, frequent assessment.

So begin to think: do you actually need this specific data point? What critical focus does it illuminate that couldn’t be served by another piece of information?

And if you decide that yes, that data point is indeed necessary… what systems can you put in place to roll its collection into your other, existing work?

At this stage in the process, your data roadmap should be coming together. You know what metrics you’ll be using to measure, how they should look at the ultimate outcome of your program, and where staff need to be at various points throughout the year to indicate you’re on the right track. The next step is to start asking staff for feedback and surveying where they are in the process, right?

Question that impulse.

Whether you realize it or not, data is all around us. Some or even all of the information you seek may already be available without your knowledge. Before you ask anything of your teachers, think carefully about what you can glean from existing records. Two sources that may be relatively trivial on their own, for example, might offer new insight when put together. Consider sources like:

Now, consider how those sources could work together:

Every question you don’t ask your respondents is one less demand on their time — which in turn clears up room for the important stuff.

Once you’ve identified the data that needs collecting, make time for it. Often, feedback is left at the end of an event or activity so that attendees are being asked to complete a survey while packing up. To truly build a feedback loop culture, build dedicated reflection time into your PD activity — and bookend it by giving out resources or closing out with next steps afterward.

Dr. Glenda Horner of Cypress-Fairbanks made this thoughtful point in her recent KickUp webcast:

If your potential respondents can clearly understand the value of their response and how it will be used, they’re much more likely to contribute their time to your survey.

Make sure to clearly connect the survey questions themselves to the purpose behind the survey, whether it’s drilling down on content approaches or creating a more equity-focused school environment.

Fast forward to 51:48 in KickUp’s 6 Common PD Data Mistakes webcast to hear Barbara Phillips of Windsor Central School District talk about how she handles top-to-bottom data buy-in for her district

The key to building long term buy-in is the following up: show your respondents the extent of their impact by articulating exactly what actions you took based on the survey results. This often has the side benefit of building a cycle of trust, where teachers become eager to share because they understand that their voices will be heard.

“Data are not taken for museum purposes; they are taken as a basis for doing something. If nothing is to be done with the data, then there is no use in collecting any.” — W. Edwards Deming, The New Economics for Industry, Government, and Education

The beauty in all of your pre-planning is that it’s created a strong foundation for the fine details of your study. Your questions should align directly with your KASABs, which in turn should align directly with your logic model.

Before launching any kind of data collection, whether it’s a feedback survey or a simple pulse check-in, read each question carefully and ask yourself “How does this directly indicate the changes I’m looking for?” If the answer doesn’t connect, rephrase or cut.

Remember: it’s always easier to prevent issues through thoughtful design now than it is to sort through a mass of fuzzy data later.

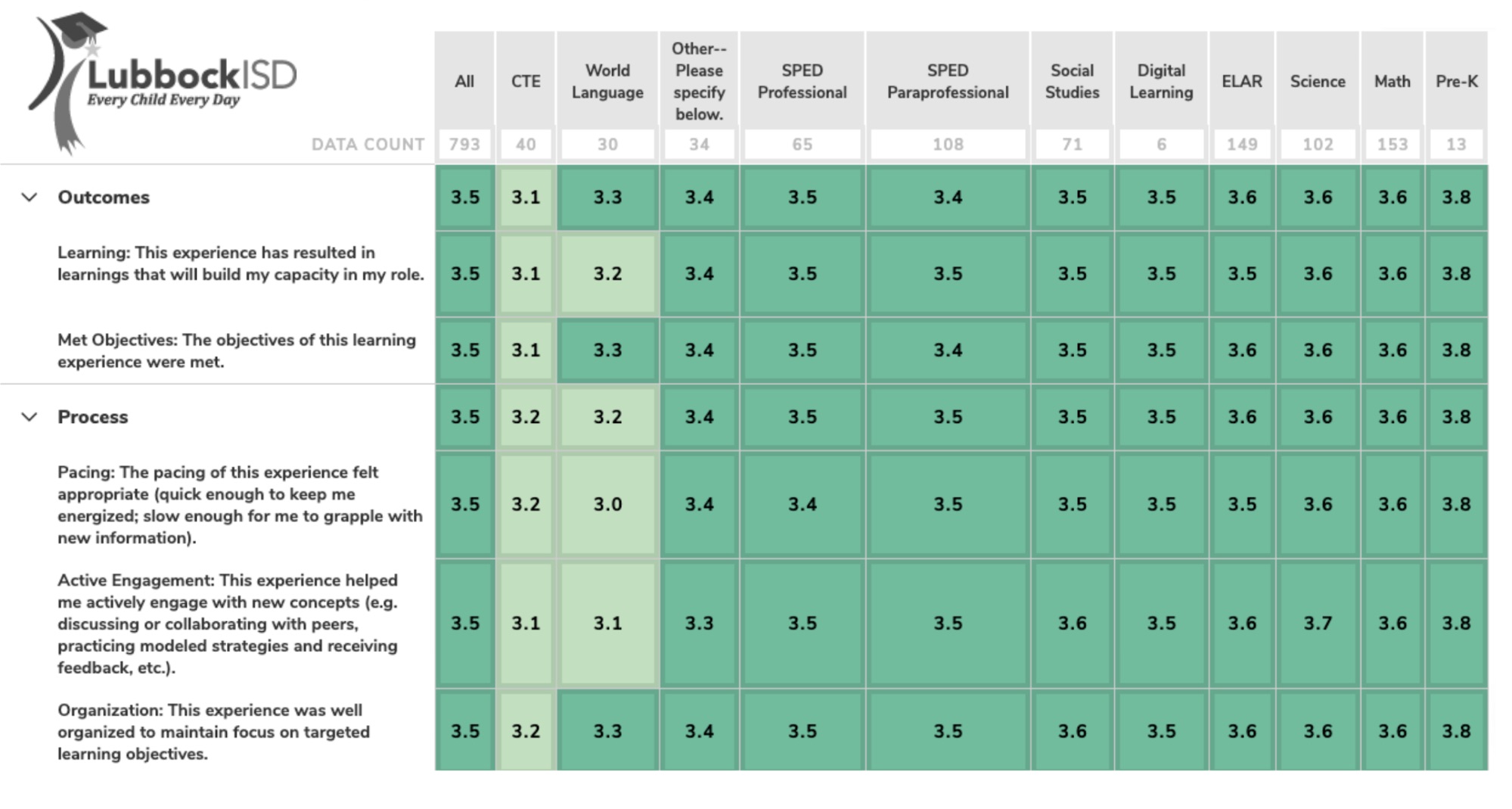

In our recent conversation on putting post-PD feedback to work, Lubbock ISD’s Anna Jackson talked about building a cycle of trust and respect in their teachers through continuous, feedback-driven improvement cycles.

With thousands of teachers to track and support, this busy Texas district can’t afford to waste time with impractical or ineffective data methodology. So instead of taking on the impossible task of mandating feedback unilaterally, she chooses to emphasize collective buy-in and respect as not just a culture initiative, but as an operational tactic to streamline the collection itself:

Anna Jackson: “One of the things that we’ve wrestled with is just making sure that people had trust enough to be able to give us quality feedback… Initially we really had to work hard to earn their trust in order to get sufficient responses, and be very clear that the data that we’re collecting was anonymous data.

We had to make a decision: is it more important to us to have very little data and know exactly who it is? (And it’s probably going to be the people who are really happy and really mad.) Or is it more important to us to have better overall data with a little less ability to filter, but be able to be more strategic in our planning and in our followup?”

Looking at their heatmap data, Lubbock administrators saw clearly that CTE (Career and Technical Education) and World Language instructors needed a little extra support in that content area.

“It’s a hard thing in a district when you’re doing training on such a large scale to be able to turn that quickly,” Jackson said. “We’ve found that people in our district are building their confidence in our data and in our responsiveness to that data, which has been really critical to getting even more feedback from them. I think they’ve been able to see ‘We said this and they did that.’”

Anna closed the feedback loop by planning for extra CTE and World Language supports in future sessions, with the promise of continuous improvement:

The big takeaway? Connecting the cultural element (deliberate trust-building) to the operational one (building intentional feedback loops into the process). Opportunities to boost your existing data mechanisms or harness them in new ways are everywhere — if you know where to look.

Schedule a demo with one of our friendly team members.